Mayor Adams summons “anti-Semitism” and “anti-American” hatred on university campus

New York City Mayor Eric Adams detailed his plans to combat rising anti-Semitism across the city’s university campuses and stressed the establishment of a new mayor’s office to fight anti-Semitism when appearing in CNN’s “Scenario Room” on Friday.

The mayor called for an increase in “anti-Semitism” and “anti-American” sentiment on the New York City University campus, noting that the two seem to be “bound together.”

Adams also spoke about the rising anti-Semitism in public schools in New York City, referring to two newsletters allegedly distributed by public schools that honored the Hamas terrorist group.

Eric Adams ruled his plan to combat immigration crime: “All part of this process”

New York City Mayor Eric Adams called for two newsletters from public schools to “give people the impression of Hamas.” (AP/Julia DeMaree Nikhinson)

“We saw two newsletters, which really made a buzzing impression on Hamas, and Hamas’ representatives,” Adams told Anchor Wolf Blitz, saying. “Hamas is a terrifying, dangerous organization that cannot be tolerated in our public school system.”

To actively discuss the issue, Adams said the city has been using a program called “Break Bread, Build Band” to unify the community against anti-Semitism.

“In the past few years, we have over 1,000 dinners, people sit down and communicate with each other and then look at printed information that has been sent to any agency within the city that has any form of procurement contracts with entities that are hated or anti-Semitism,” Adams said. “It’s really, not only a reaction to the case that comes, but also proactive.”

Click here for more media and cultural reports

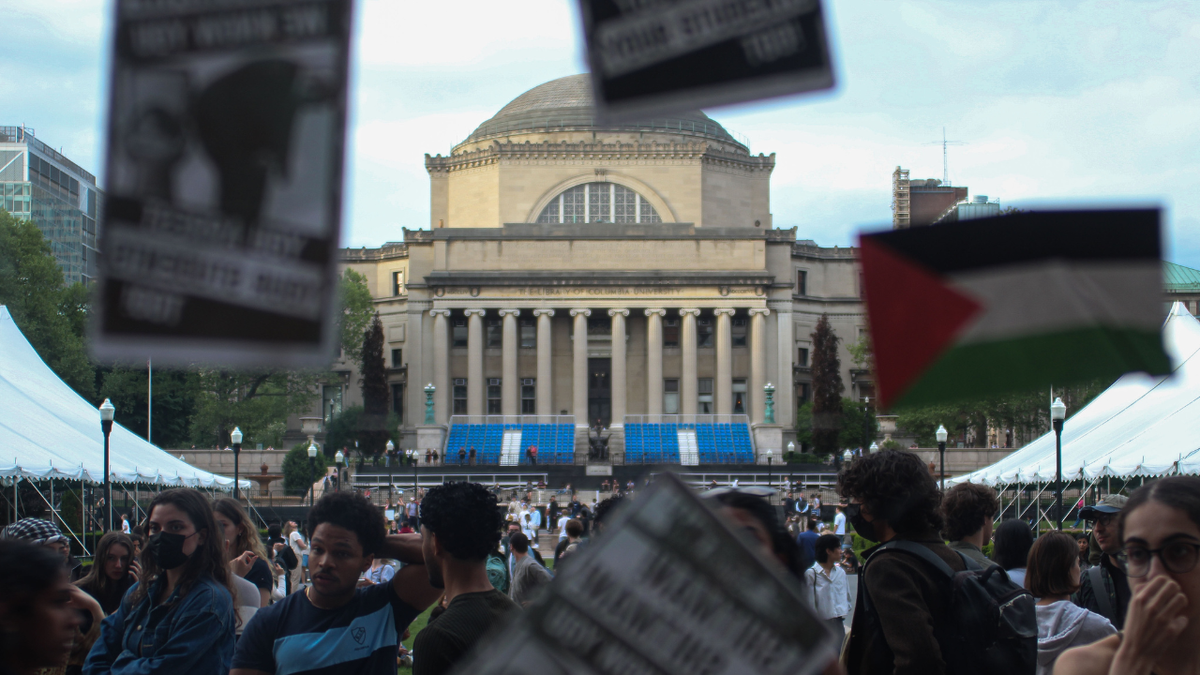

Columbia University in New York City has become a hotbed of anti-Israel protests following the Hamas attack. (Indy Scholtens/Getty Images)

Blitzer asked Adams what his criticism of free speech activists were, criticizing foreign students attending American universities for expressing their “pro-Palestine” views and how he would ensure that students' First Amendment rights are protected while also protecting anti-Semitism.

“Well, think about it, wolf,” Adams replied. “Last year, after the October 7 attack, we conducted more than 3,000 protests and 3,000 people were able to express their concerns and exercise their right to freedom of speech.”

Adams continued: “This city, when you look at all kinds of protests, exercise freedom of speech, people express their opinions with 8.5 million people, we do this in an orderly manner. We allow people to do this. You can look at the marches that are happening in this city because it is what we believe, because it is our freedom of speech, it is a city with free speech, and it is important.” It is important. ”

Click here to get the Fox News app

The Trump administration cut $400 million in federal grants to Columbia University in New York in March as fears of increased anti-Semitism on campuses.

In May, the university announced it would lay off about 180 employees in response to fund cuts.